Cultural Backgrounds and Aversion: How Superstitions Shape Our Perceptions in Different Societies | 文化的背景と忌避感:異なる社会における迷信がもたらす認識の変化

Do Americans dislike the number 13!?

In the condominium where I live, there is no 13th floor. In Japan, there are also instances where parking lots lack spaces numbered 4 or 9. I have summarized the reasons for this based on my research with ChatGPT.

1. Why Are There No 13th Floors in American Condominiums?

The reason why some American condominiums and hotels lack a 13th floor stems from the Western cultural superstition that views the number 13 as unlucky. This is related to a fear known as "triskaidekaphobia," where many people consider 13 to be a symbol of misfortune. This superstition became particularly widespread in Christian cultures. The background consists of the following three factors:

-

The Last Supper: At the "Last Supper," which took place the night before Jesus Christ was crucified, there were 13 attendees, with Judas, who betrayed Christ, sitting in the 13th seat.

-

Friday the 13th: "Friday the 13th" is considered an unlucky day, particularly due to the events of October 13, 1307, when King Philip IV of France arrested the Knights Templar, reinforcing this superstition.

-

Influence of Ancient Cultures: The number 12 is often viewed as a symbol of completeness, so the number 13 is perceived as representing instability or chaos.

Due to this cultural background, there is a tendency in America to avoid the number 13 in building floors. It is common for elevator buttons to skip from 12 to 14, treating the 13th floor as nonexistent. This is similar in hotels and condominiums, where the 13th room is often avoided as well. While many people may not be bothered by this superstition, building owners and designers frequently choose not to use the number 13 to avoid unsettling or anxious guests. Thus, the practice of avoiding the 13th floor continues due to psychological considerations and commercial reasons.

2. What About Japan?

In Japan, there is not as strong a sense of aversion toward the number 13. While there may be cases in Western-style hotels or buildings where the 13th floor is avoided, it is not common. On the other hand, in Japan, the numbers "4" and "9" are often avoided as they are considered unlucky. This is because the pronunciations of these numbers sound similar to "death" and "suffering."

Firstly, "4" is pronounced as "shi," which sounds like the word for "death," giving it an unlucky connotation for many people. Therefore, rooms numbered 4 and floors numbered 4 are often avoided in hospitals, hotels, and condominiums, and it is common to skip space number 4 in parking lots as well.

Next, "9" is pronounced as "ku," which evokes associations with "suffering" or "pain," and thus is similarly avoided. Particularly in hospitals, the number 9 is often associated with misfortune, making it common for rooms or floors numbered 9 to be nonexistent. Additionally, combinations such as "49" or "42" can be read as "death" or "death pain," making these also considered unlucky.

For these reasons, the numbers 4 and 9 are avoided in Japan, especially in situations where auspiciousness is important or where mental peace is emphasized. This has become a cultural habit, rooted in tradition, to prioritize psychological comfort by avoiding these numbers.

3. Taboos in Visiting Patients in Japan

From the perspective of sound, "cyclamen" tends to be avoided as a gift for patients. In Japanese, cyclamen is pronounced "shikuramen," which includes the sounds for "death" and "suffering."

In other countries, however, cyclamen often symbolize "affection," "healing," and "sincerity," and can convey a positive impression. Regarding flowers given when visiting patients, camellias are also avoided in Japan. This is mainly because the way the flowers drop evokes the image of "heads falling," which is considered unlucky. Conversely, overseas, camellias are seen positively, symbolizing "nobility," "beauty," "longevity," and "love," so one might want to be mindful of the type of flowers when visiting.

4. Summary and Reflections

I gained a better understanding of how cultural backgrounds lead to different aversions. In America, the avoidance of the number 13 is influenced by religious and historical contexts, while in Japan, the aversion is based on sound symbolism, which I found interesting. Although I focused solely on the culture of the United States where I live, I believe that other countries may show aversions to entirely different things.

Such subtle cultural differences, especially regarding negative connotations, can lead to misunderstandings about others’ behaviors if one is not aware of these cultural backgrounds. I think it’s important to recognize that there are cultural and historical contexts that I have never considered in my own life.

This applies not only to different countries but also among citizens within the same country. I dislike the word "common sense." People who say, "This is common sense," often assume that what they know is something that most people know, reflecting a sense of pride in living among the majority. I want to live with the awareness that the path I have taken is just one of many, and that there are many different paths that people have walked, each with its own culture and background.

*************************************

アメリカ人は13が嫌い!?

私の住んでいるマンションには、13階がありません。

日本でも、駐車場に4番や9番がないことがあります。

この理由について、ChatGPTで調べた結果を中心にまとめました。

1. なぜアメリカのマンションに13階がないのか

アメリカで「13階がないマンション」やホテルがある理由は、13という数字が不吉とされる西洋文化の迷信に由来しています。これは「トリスカイデカフォビア(triskaidekaphobia)」と呼ばれる13恐怖症に関連し、多くの人々が13を不運の象徴と考えています。この迷信は、特にキリスト教圏で広まりました。

その背景は以下の3つの要因に基づいています。:

-

最後の晩餐: イエス・キリストが十字架にかけられる前夜の「最後の晩餐」に13人が参加し、13番目の席に座ったのがキリストを裏切ったユダだった。

-

13日の金曜日: 「13日の金曜日」は不運の日とされており、特に1307年の10月13日(金曜日)にフランス国王フィリップ4世がテンプル騎士団を逮捕した事件がこの迷信を強化した。

-

古代文化の影響: 12が完全性を象徴する数字とされており、13はそれを超えて不安定や混乱を意味するものとして捉えられている。

こうした文化的背景から、アメリカでは建物の階数に13を避ける傾向があります。エレベーターのボタンでは、12階の次に14階が表示され、13階は存在しない扱いになることが一般的です。これはホテルやマンションでも同様で、特にホテルでは13号室も避けられることが多いです。多くの人はこの迷信を気にしないかもしれませんが、建物のオーナーや設計者は不快感や不安を抱く客を避けるため、13という数字を使用しないことが多いのです。このように、13階を避ける慣習は心理的配慮や商業的な理由から続いています。

2. 日本ではどうか

13に関してはそれほど強い忌避感はありません。西洋風のホテルや建物で、13階を避けるケースはあるかもしれませんが、一般的ではありません。一方で、日本では、「4」と「9」が不吉とされる数字として避けられることがあります。これは、これらの数字の発音が「死」や「苦」と同じ音になるためです。

まず、「4」は「シ」と発音され、「死」という言葉と同じ音になるため、多くの人々にとって不吉な印象を与えます。このため、病院やホテル、マンションなどでは4号室や4階が避けられることが多く、駐車場のスペースでも4番を飛ばすケースがあります。

次に、「9」は「ク」と発音され、「苦しみ」や「苦痛」を連想させるため、同様に避けられる傾向があります。特に病院では「9」という数字が不幸を連想させるため、9号室や9階が存在しないことが一般的です。また、「49」や「42」といった組み合わせも「死に」や「死苦」と読めるため、これらも不吉とされます。

これらの理由から、日本では4や9が避けられ、特に縁起を担ぐ場面や、心の平安が重視される場所でこの傾向が強く見られます。文化や習慣として根付いており、心理的な安心感を優先するために、これらの数字を避ける習慣が広がっています。

3. 日本におけるお見舞いのタブー

音の響きの観点から、患者へのお見舞い品として、「シクラメン」が避けられる傾向にあります。日本語でシクラメンは”Shikuramen”と発音され、「死」「苦」が含まれるからです。

他の国では、シクラメンは「愛情」「癒し」「誠実さ」などを意味し、むしろポジティブな印象を与える場合も多いそうです。

お見舞い時の花に関しては、日本では椿も避けられる傾向にあります。特に花がぽとりと落ちる様子が「首が落ちる」ことを連想させるため、不吉だとされます。椿に関しても海外では、「高貴」「美」「長寿」「愛」などポジティブな印象があるようですので、お見舞いに行く場合には花の種類には気を付けた方がいいかもしれません。

4. まとめと感想

文化的背景によって、忌避するものが異なることがよく理解できました。アメリカでは13に関しては、宗教及び歴史的な背景から忌避されていますが、日本では、音の響きによって忌避されているという点も、違いがあって面白いなと思いました。今回は私が住んでいるアメリカにのみフォーカスしましたが、違う国では、また全然違うものに忌避感を示す場合もあると思います。

このような細かい文化の違い、特にネガティブな意味を持つ文化の違いは、その文化を知らずに行動してしまった相手のことを悪く思ってしまうこともあるかもしれません。自分の生きている世界では考えもしなかった文化や背景があることを知ることが大事だと思いました。

国の違いに限らず、同じ国の国民であっても同様だと思います。私は「常識」という言葉が嫌いです。「これは常識だ」という人は、自分が知っていることは大抵の人が知っている、自分は多数派の中に生きている、という自負があるように思います。自分の生きてきた道は一つであり、他にも多種多様な道があって、それぞれの道を歩んできた人がいて、そこにはそれぞれの文化や背景がある、ということを、私は忘れないように生きていきたいと思います。

※英文は上記日本文を基にChatGPTで作成しました。

The English text was created based on the above Japanese text using ChatGPT.

When the Familiar Turns Unfamiliar: The Challenges of Life Abroad | 普通が普通でなくなるとき:海外生活の苦労

Living in Another Country: The Challenges

My mother came to visit me from Japan last week. We went to Wholefoods Market to buy ketchup for my daughter's school sports day lunch. But we couldn't find the small packets of ketchup there.

When my mother said she almost found it in the ketchup section in Japan, I remembered my early days in the US. At first, I felt stressed because I couldn't do simple things that were easy in Japan.

For example, in Japan, I knew without thinking where to buy things:

- Groceries at the supermarket

- Makeup and home goods at the drugstore

- Electronics at the electronics store

I could quickly decide what food was good for kids and what skincare products were safe for sensitive skin. I knew which banks to use and how to set up gas and electricity services.

I knew almost everything about daily life in Japan and could easily get information in Japanese. But in a new country, I didn't know these simple things.

Every day was a struggle, and I felt very tired doing normal tasks. Now, I feel less stress. I'm used to life here. I know where to buy groceries, and I can use Amazon for most things. (I'm very thankful for Amazon!)

But for unexpected events like accidents, I would still be very confused about what to do.

Understanding how hard it is to live a normal life in another country is a valuable experience for me. I want to help people from other countries who have trouble getting used to life in Japan.

***************************************

先日母が日本から遊びに来ていました。

娘の運動会のお弁当準備のために、小分けになったケチャップが欲しいなと思ってホールフーズに一緒に行ったのですが、結局見つかりませんでした。

母は、日本だったら、スーパーのケチャップ売り場に小さいのだいたいあるのにね、と言っていて、渡米当初の苦労を思い出しました。

海外で暮らし始めたとき、今まで当たり前にしていたことが、当たり前にできなくなることにストレスを感じました。

例えば、日本で生活していたら、考えなくても、

- スーパーマーケットで食料品を買う

- ドラッグストアで化粧品や日用品を買う

- 家電量販店で電化製品を買う

というものだとわかります。

これは子供でも食べられる、この化粧品は敏感肌向けだから安心して使えそう、なども瞬時に判断できます。

生活のインフラに関しても、銀行口座はここで開設できる、電気ガスの開通はここに連絡すればよい、なども身についている場合が多いです。

日本での日常生活に必要なことはだいたい知っていましたし、日本語で簡単に情報を得ることができましたが、新しい国では、そんな簡単なことすらもわからない。

そういう、今まで行っていた当たり前が当たり前でなくなり、労力がかかることが本当に大変でした。

今では、大体買い物はここに行くとか、アマゾンで買える(アマゾンには本当に感謝しています)とか、生活することへの苦労はだいぶなくなりました。

ですが、突発的な出来事に関しては、対応に苦労することもまだまだたくさんあります。

他国で普通の生活を送るということがこんなにも大変だということを理解できたことは、私にとってとても良い経験になりました。

他の国から来て、日本で生活をしている方で困っている方がいたら、助けてあげたいと思いました。

Exploring Raw Food Culture in Japan and Around the World: A Surprising Culinary Experience | 日本と世界の生食文化 〜驚きの食体験〜

Have you ever eaten Raw Chicken ?

I sometimes attend a free English conversation class at the public library. The class has 2 library staff and 8-16 people from different countries who sign up. Everyone is very friendly, and you can join on the days that are convenient for you.

***********************************

私は、たまに英会話のグループクラスに参加することがあります。

公立図書館主催で無料です。

2人の図書館職員と8〜16人程度の、その時々で登録した様々な国のメンバーで、オンラインで開催されます。職員が出すお題に対して、各々の意見を述べるというものです。1時間程度なのですが、毎回2〜4テーマくらい話します。

先日のお題の一つに、食べたことのあるゲームミートはなんですか?という問いがありました。

ゲームミートとは、ワニやカンガルーなど、通常食される肉以外の肉のことです。

日本ではジビエ料理として、鹿や猪などを食しますが、わたしはあまり食べたことがなかったので、馬の肉の刺身だと答えました。日本人は寿司や刺身など、生で食べることが好きだから、鶏も生で食べる(鳥刺し)と答えたら、参加者全員から驚かれました。私は馬刺しも鳥刺しも好きです。

海外ではあまり生食は好まれないようで、このお題に中国出身の参加者は、生のタコを食べて、口の中で動いて気持ち悪かったと答えていました。私は生のタコもイカもエビも食べたことがありますが、醤油をつけるとうねうね動いたり、口の中で吸い付かれる感じがあったりして、ちょっと気持ち悪いです。この話も、かなり驚かれました。

では、日本ではいつから生の食べ物を食べるようになったのでしょうか?ChatGPTに聞いてみました。

日本では、古代から生魚を食べる文化があり、特に刺身や寿司として広まりました。平安時代(794〜1185年)にはすでに刺身があり、江戸時代(1603〜1868年)には「なれ寿司」という保存食から、現在のような生の魚を乗せた握り寿司が誕生し、江戸前寿司として発展しました。一方、生肉を食べる習慣は、明治時代(19世紀後半)以降、西洋文化の影響で広まりました。それ以前は仏教の影響で肉食が禁止されていたため、生肉の文化はありませんでした。しかし、明治政府が肉食を奨励したことで、ユッケや牛刺しといった生肉料理が20世紀以降に登場しました。

生肉を食べる文化は、他の国と比べて比較的新しいスタイルであり、独自の日本食文化として発展してきたことがわかりました。

お腹を壊さないように気をつけて、生の食べ物を楽しんでくださいね!

The Mystery of Thin-Sliced Meat in American Grocery Stores : アメリカのスーパーに薄切り肉がない謎

The Mystery of Thin-Sliced Meat in American Grocery Stores

Hello, everyone!

What kind of meat do you like to eat or cook? Personally, I'm a big fan of pork, especially thinly sliced pork belly. In Japan, I often cook "yasai itame," a simple stir-fry dish with cabbage, sliced onions, and thin-sliced pork, seasoned with just salt and pepper.

However, when I moved to the United States, I was surprised to find that thinly sliced meat, both pork and beef, is hardly available in grocery stores here! I frequently make special trips to distant supermarkets specifically to purchase thin-sliced meat. On the rare occasions when I do find it at nearby stores, I make sure to buy it immediately.

On the flip side, American grocery stores offer a wide variety of beef cuts for steaks, large blocks of meat (similar to what we'd use for roast beef or Chinese-style roasted pork in Japan), and various types of ground meat.

Curious about this difference, I decided to ask Claude 3 why stores in the US rarely sell thinly sliced meat. Here's what I learned:

- Culinary culture differences: Japanese cuisine includes many dishes that use thin-sliced meat, such as shabu-shabu and yakiniku. In contrast, traditional American cuisine often uses thicker cuts of meat for dishes like steaks and roasts.

- Cooking methods: Japanese cooking often involves quick-cooking techniques, for which thin-sliced meat is ideal. American cooking frequently uses grilling or oven-roasting methods that are better suited to thicker cuts of meat.

- Food culture history: Historically, Japan consumed less meat, leading to the development of cooking methods that efficiently use small amounts of meat. The US, with its abundant cattle farming, developed a culture of cooking larger pieces of meat.

- Utilization of meat cuts: In Japan, it's common to thinly slice various parts of the animal for use in different dishes. In the US, specific cuts are often associated with particular cooking methods.

- Retail systems: Japanese butcher shops commonly slice meat thinly upon customer request. US supermarkets typically sell pre-packaged meat cuts.

- Consumer preferences: American consumers generally prefer thicker cuts of meat, reflecting cultural differences in texture and satisfaction derived from meat consumption.

While I'm not entirely convinced about reason #5, the others seem quite plausible. In fact, my kitchen came with a built-in oven, which is common in most American homes. Americans also seem to prefer barbecue, which is a bit different from Japanese-style grilling.

Right : American-style grill I often see here

So, I can understand why there's such a variety of large meat cuts in American grocery stores. When I first arrived in the States, I really struggled with not being able to find thinly sliced meat. However, I've recently learned to manage my cravings by using chicken and ground meat as alternatives.

In the future, I hope to share more about how I cook and eat using the ingredients available in American stores. It's been an interesting culinary adventure!

Thank you for reading today's post.

**************************************************

アメリカのスーパーに薄切り肉がない謎

みなさん、こんにちは!

みなさんはどんなお肉を食べたり料理したりするのが好きですか?私は豚肉が大好きで、特に薄切りの豚バラ肉がお気に入りです。日本では、キャベツ、スライスした玉ねぎ、薄切り豚肉を塩コショウだけで炒める「野菜炒め」をよく作っていました。

ところが、アメリカに引っ越してきて驚いたのが、スーパーでほとんど薄切り肉(豚肉も牛肉も)が売っていない!わざわざ遠くのスーパーに、薄切り肉を求めて出かけることすらありますし、たまに近所の店で見つけたときは、必ず買うようにしています。

一方で、アメリカのスーパーには、ステーキ用の様々な部位の牛肉や、日本でいうローストビーフや中華風チャーシューに使いそうな大きなブロック肉、そして様々な種類のひき肉がたくさん並んでいます。

この違いが気になって、なぜアメリカの店では薄切り肉をほとんど売っていないのか、Claude 3に聞いてみました。以下が、その回答から学んだことです:

- 料理文化の違い:日本料理には、しゃぶしゃぶや焼肉など、薄切り肉を使う料理が多くあります。対照的に、アメリカの伝統的な料理では、ステーキやロースト料理など、厚切りの肉をよく使います。

- 調理方法:日本料理では短時間で調理する技法が多く、薄切り肉に適しています。アメリカ料理では、グリルやオーブン焼きなど、厚切り肉に適した調理法をよく使います。

- 食文化の歴史:歴史的に、日本では肉の消費量が少なく、少量の肉を効率的に使う調理法が発展しました。一方、アメリカでは牧畜が盛んで、大きな肉の塊を調理する文化が発展しました。

- 肉の部位の使い方:日本では、動物の様々な部位を薄く切って異なる料理に使うのが一般的です。アメリカでは、特定の部位が特定の調理法と結びついていることが多いです。

- 小売システム:日本の精肉店では、客の要望に応じてその場で肉を薄く切ることが一般的です。アメリカのスーパーマーケットでは、通常、パック詰めされた肉を販売しています。

- 消費者の好み:アメリカの消費者は一般的に厚切りの肉を好む傾向があり、これは肉の食感や満足感に関する文化的な違いを反映しています。

理由の5番目については理解しかねるところがありますが、他の理由はとても納得できるものでした。実際、私の家のキッチンにはオーブンが最初から設置されていたし、アメリカの家ではほとんどがそうだと思います。アメリカ人はバーベキューも好きなようですが、少し日本のものとは違っています。

このように、アメリカのスーパーに大きな肉の塊が多く並んでいる文化にも納得がいきます。アメリカに来た当初は薄切り肉が手に入らないのが本当に辛かったのですが、最近では鶏肉やひき肉を使って薄切り肉が食べたい欲求を抑制できるようになりました。

機会があれば、アメリカの店で手に入る食材を使って日常的にどんな料理を作って食べているか、ご紹介したいと思います。

ここまで読んでいただき、ありがとうございました。

Quick and easy lunch : 時短簡単ランチ

Hi, everyone.

What's for lunch today?

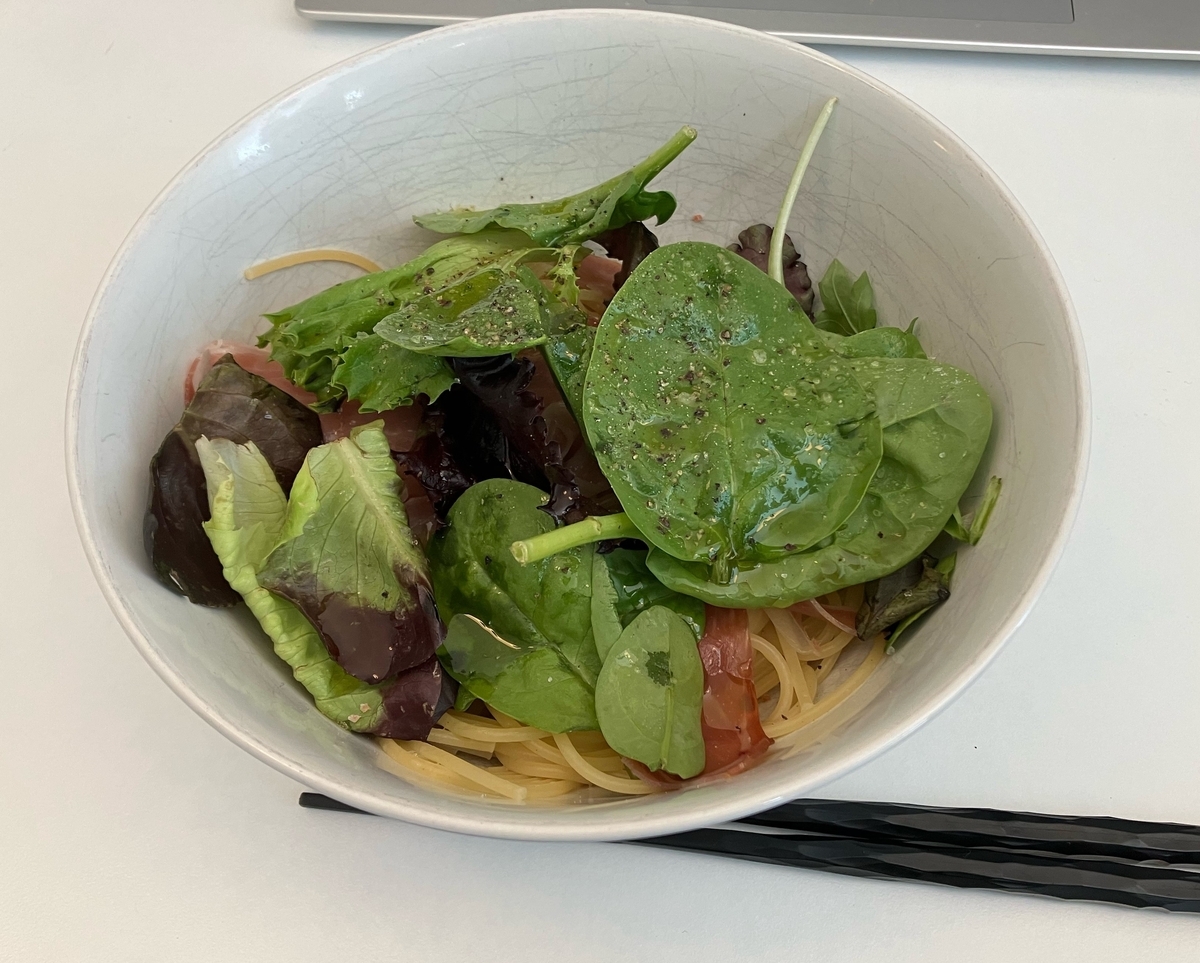

I often eat quick meals while my daughter is at kindergarten and I'm home alone. Today’s lunch is prosciutto pasta, the same as yesterday. Recently, I've been cooking pasta in the microwave.

Here’s how I do it:

1. I prepare a microwave-safe deep bowl, like a donburi bowl in Japan, about 80-100g of pasta, and hot water to fill the bowl.

2. I put the water and pasta in the bowl and set the microwave time according to the instructions on the pasta package.

3. After cooking, I drain the water and add olive oil, salt, pepper, some salad leaves, and prosciutto.

The pasta I use the most is spaghettini, which is about 1.3mm in diameter, and the second most is linguine, which is flat, like pho noodles in Vietnam or kishimen in Japan. My microwave has a power of 1000W, and I usually succeed in cooking pasta this way.

It might not be photogenic, but I’m satisfied with it because I don’t need a photogenic meal for my daily lunch—I’m just happy to eat.

Back in Japan, I often bought lunch at nearby convenience stores or ate frozen meals. They were so delicious and affordable that I didn’t feel the need to learn how to cook quickly and easily. However, dining out or getting takeout in America is expensive, so I make an effort to cook for myself every day. Cooking daily helps me save money, which I can then spend freely when I travel or go out.

Have a good day with ease!

*********************************

みなさんこんにちは。

今日のランチはなんですか?

私は、娘が幼稚園に行っている間に一人でランチを食べるときは、簡単に済ますことが多いです。

今日のランチはプロシュートパスタでした。昨日もでしたが笑

最近は、一人分の乾燥パスタなら電子レンジで茹でてしまうことが多いです。

耐熱ボウルまたは丼に、パスタ80〜100gと70℃くらいの温かめのお湯を可能な限りたくさん入れて、電子レンジで表記の時間セットします。

私はスパゲッティーニという種類のパスタ(1.3mmくらい?)を使って、1000W(これが一般的)のレンジで表記通りでいけました。リングイネという日本でいうきしめんみたいな平たいパスタだと、+1分くらいです。

それにオリーブオイル、適当なサラダ葉っぱ、塩胡椒とプロシュートを乗せて完成です。

全然映えませんが、昼ごはんはお腹が満たせれば良いタイプなので、全然いいです。

日本にいたときは、近くにコンビニがあったり、美味しい冷凍食品があったりして、安くて簡単にご飯が食べられたので、あまりこういう簡単調理について探求してなかったのですが、アメリカでは外食や買飯が高いので、自炊の価値が高いです。日々の自炊で節約して、旅行やお出かけの時に気兼ねなくお金を使いたいので、適当に頑張ってます。

楽していきましょう!ありがとうございました。

The Differences in Return Cultures Between Japan and the U.S. : 日米の返品文化の違い

-

Introduction

Hello everyone! Have you ever returned a product? I've experienced returning items several times in Japan, mainly clothes. After having a child, I had less time for shopping and started buying more online. However, without being able to try things on in-store, sometimes online purchases didn't match my expectations or fit properly. - Return Policies in Japan

In Japan, returning items can be challenging. There are often strict requirements: tags and packaging must be intact, customers must pay return shipping, and prior contact is necessary before returning. Also, products like cosmetics can't be returned once used, even if they don't suit your skin or the color isn't right. Because of this, I would often try cheaper secondhand items first or carefully research reviews before purchasing. - Return Policies in America

Since coming to America, I've returned items more frequently. I often return products from Amazon, including fresh food from Amazon Fresh, cosmetics, and fashion items from online shopping. It's common to buy something without being sure if it fits and return it if it doesn't. This applies to sale items too. I've been able to return used cosmetics like lip gloss and shoes I wore for two days, even without the box. In Japan, returning such items would usually be impossible.

The return process is very simple, especially with Amazon. You just go to the returns page, select the item and reason for return, choose your refund method and return option, then get a QR code and take the item to a specified store. This process is so straightforward that you don't need to be fluent in English to complete it. - Background of Different Return Cultures in Japan and America

Why is returning items so easy in America but difficult in Japan? Let's consider the historical background and cultural differences. The following is quoted from ChatGPT4:

Consumer Culture Differences:

In America, a consumer-driven culture is deeply rooted. After World War II, America transitioned to a mass production and consumption society, forming a culture where consumers freely purchase and return products. Companies adopted return policies to build trust with consumers, which became a standard service.In contrast, Japan has a strong 'mottainai' (waste-not) spirit, which has created a culture of treating purchased items with care and not returning them easily. Japanese companies often consider returns as potentially damaging to their product or company reputation, so they typically set strict return conditions.

Business Practices and Customer Service Differences:

In America, the idea that 'the customer is always right' is widely accepted, and companies prioritize customer satisfaction. This leads to a tendency to make returns easy, even when customers are dissatisfied with products.

In Japan, high quality and service are expected from sold products. Therefore, even when returns are necessary, consumers often feel it's their fault. Companies also prioritize product reliability and may view accepting returns as potentially damaging to that reliability.

Legal and Institutional Background:

In America, laws and regulations regarding returns are set favorably for consumers. For example, the 'cooling-off' system gives consumers the right to return products within a certain period for any reason.

In Japan, while there are laws regarding returns, companies are given some discretion, and strict conditions are often set for returns due to 'customer circumstances.'

Trust Relationships and Social Expectations:

In Japan, strong trust relationships are built between companies and customers, and behavior that doesn't damage this trust is expected. Returns may be seen as questioning product satisfaction or reliability, so consumers carefully consider such actions. There's also a culture where returning items is seen as 'impolite,' leading consumers to hesitate about returns."

- Return Policies in Other Countries Return cultures differ in other countries too.

In European countries, returns are relatively easy, but there are subtle differences between countries. In the UK, there's a legally mandated 14-day 'cooling-off' period where returns are accepted for any reason. Germany also has strict consumer protection regulations, making returns easy, but due to high quality expectations, purchasing behavior tends to be cautious.

In China, return policies have become more flexible with the spread of online shopping, but negotiations with companies are often necessary when returns are needed.

- What Happens to Returned Items in America? What happens to returned items in America?

- Resale:

Many returned items are resold. Unused or good condition items may be sold as 'open box' or 'outlet' items at discounted prices. Some are sold to third-party vendors for sale in different markets. - Refurbishment:

Especially for electronics and expensive items, they undergo inspection, repair, and cleaning before being resold as 'refurbished' items. These are popular with consumers as they're cheaper than new items. - Donation or Disposal:

Some returned items are donated to charities or non-profit organizations. Items difficult to resell or refurbish, especially food or cosmetics that can't be reused for hygiene reasons, may be disposed of. Recently, efforts towards recycling have increased due to environmental concerns.

- Conclusion

This is an analysis of the differences in return cultures between America and Japan, as well as return situations in other countries. We can see that consumer culture, business practices, laws, and social expectations in each country are deeply involved in shaping return cultures. Through this investigation, I've come to understand the mindset towards returns and the ease of the process in America.

Thank you for your attention.

****************************

1.はじめに

こんにちは、皆さんは返品をしたことがありますか?私はこれまでに、日本で何度か返品を経験しました。主に衣類の返品です。子供が生まれてからはショッピングの時間が減り、オンラインでの買い物が増えました。しかし、実店舗で試着しない分、オンラインではイメージと異なったり、サイズが合わなかったりすることもありました。

2.日本の返品事情

ただ、日本では返品には高いハードルがあると感じます。タグやパッケージがそのままでなければならない、返送料が自己負担、返品する前に連絡が必要など、手続きが煩雑です。

また、化粧品のような一度使ってしまった商品は、肌に合わなかったり色が合わなくても、返品はできません。そのため、事前にメルカリで安く試したり、口コミサイトやYouTubeのレビューを参考にして、慎重に購入していました。

3.アメリカの返品事情

一方、アメリカに来てからは、返品の経験が増えました。Amazonをはじめ、Amazon Freshでの生鮮食品、化粧品やファッションブランドのオンラインショッピングでも頻繁に返品しています。

サイズが合うかわからなくても、とりあえず購入し、合わなければ返品するのが当たり前になっています。セールで買った商品も同様です。

これまでに返品した商品は、例えば、リップグロスのように口に直接触れる化粧品でも返品できましたし、Amazonで買った靴も、2日ほど使用して使用感があり、外箱を捨ててしまっていたにもかかわらず、問題なく返品できました。このような商品では、日本では返品できないことが多いと思います。

返品手続きも非常に簡単で、特にAmazonでは、返品受付ページから簡単に手続きが可能です。返品する商品と理由を選択し、返金方法を選び、返品方法を選んだら、QRコードを取得して指定の店舗に持っていくだけです。こうしたプロセスは簡単で、特に英語が堪能でなくても問題なく進められます。

4.日米の返品文化の違いの背景

このように、アメリカでは返品が非常に簡単にできる一方で、日本ではなぜハードルが高いのでしょうか?歴史的背景や文化の違いを考えてみましょう。以下はChatGPT4からの引用です。

”

・消費者文化の違い

アメリカでは、消費者主導の文化が根付いています。第二次世界大戦後、アメリカは大量生産・大量消費の社会に移行し、消費者が自由に商品を購入し、返品できる文化が形成されました。企業は消費者との信頼関係を築くため、返品を受け入れる政策を取り入れ、これが標準的なサービスとなりました。

一方で、日本には「もったいない」の精神が根強く、この思想は購入したものを大切に扱い、簡単には返品しないという文化を形成しています。また、日本の企業は、返品が商品や企業の信用を損なうと考えることが多く、返品には厳しい条件が設けられることが一般的です。

・商慣習と顧客サービスの違い

アメリカでは「顧客は常に正しい」という考え方が広く浸透しており、企業は顧客満足度を最優先します。このため、顧客が商品に満足しない場合でも、返品を容易にする傾向があります。

日本では、販売される商品に高い品質とサービスが期待されており、そのため、返品が必要な場合でも消費者は自分に非があると感じることが多いです。また、企業は商品の信頼性を重視しており、返品を受け入れることがその信頼性を損なうと考えることが少なくありません。

・法的・制度的背景

アメリカでは、返品に関する法律や規制が消費者に有利に設定されています。例えば、「クーリングオフ」制度により、消費者は一定期間内であれば理由を問わず返品できる権利があります。

一方、日本では、返品に関する法律はあるものの、企業側にある程度の裁量が認められており、「顧客都合」での返品には厳しい条件が設けられることが多いです。

・信頼関係と社会的期待

日本では、企業と顧客との間に強い信頼関係が築かれており、その信頼を損なわないような行動が期待されます。返品は、商品に対する満足度や信頼性に疑問を持つ行為と見なされることがあり、消費者はその行動を慎重に考えます。また、社会的にも返品をすることが「礼儀に反する」と感じる文化があるため、消費者は返品を躊躇する傾向があります。

5.他国の返品事情

他の国々でも、返品に対する文化は異なります。

・ヨーロッパ諸国

ヨーロッパ諸国では返品が比較的容易ですが、国ごとに微妙な違いがあります。イギリスでは、購入後14日以内であれば理由を問わず返品できる「クーリングオフ」期間が法律で定められています。ドイツでも消費者保護の規制が厳しく、返品が容易ですが、品質に対する期待が高いため、慎重な購買行動が取られます。

・中国

中国では、オンラインショッピングの普及に伴い、返品政策が柔軟化していますが、返品が必要な場合でも企業との交渉が必要になることが多いです。

6.アメリカで返品された商品の行方

アメリカで、返品された商品はどうなっているのでしょうか?

・再販売

多くの返品商品は再販売されます。未使用または良好な状態の商品は、「オープンボックス品」や「アウトレット品」として割引価格で販売されることがあります。また、サードパーティ業者に売却され、別の市場で販売されることもあります。

・リファービッシュ

特に電子機器や高価な商品は、検査、修理、クリーニングを経て「リファービッシュ品」として再販売されます。これらは新品よりも安価で提供され、消費者に人気があります。

・寄付や廃棄

一部の返品商品は、チャリティ団体や非営利団体に寄付されます。再販売やリファービッシュが困難な商品、特に衛生上の理由で再利用できない食品や化粧品などは廃棄されることがあります。最近では環境への配慮から、リサイクルなどの取り組みも進んでいます。

”

7.まとめ

以上が、アメリカと日本の返品文化の違いや、他国の返品事情についての考察です。返品文化の背景には、各国の消費者文化や商慣習、法律、社会的期待が深く関わっていることがわかります。今回の調査を通じて、アメリカでの返品に対する考え方や手続きの容易さを理解することができました。

お付き合いいただきありがとうございました。